How Should Central Banks Respond to Shifting Public Perceptions on Inflation? An Interview with Adi Sunderam

Oct. 21, 2024

As inflation surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Federal Reserve found itself in a delicate balancing act—managing public expectations while confronting economic uncertainty. Harvard’s Adi Sunderam sheds light on how market participants initially underestimated the Fed’s response to inflation and why policy actions, not just words, were crucial in shifting public perceptions.

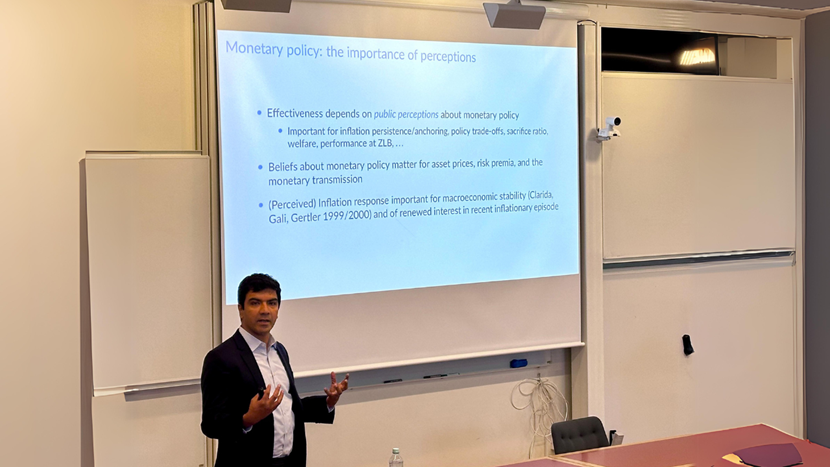

Can you start by explaining your research and why understanding changing perceptions in monetary policy is so crucial today?

In “Changing Perceptions and Post-Pandemic Monetary Policy”, we use data on the expectations of professional forecasters and data from bond markets to study how market participants thought the Federal Reserve would react to high inflation between 2020 and 2024. We find that even after inflation rose substantially, market participants anticipated a limited response from the Fed. It was only after the Fed started raising rates in early 2022 that market perceptions changed. These findings are important because public perceptions of how monetary policy will evolve are a key channel through which policy influences long-term interest rates and hence the real economy.

How has the Federal Reserve's approach to inflation evolved since the pandemic, and what insights does your paper offer about its future moves?

Our paper is mostly about public perceptions as opposed to the Fed's approach itself. In other words, the Fed's approach may have been quite consistent through the pandemic--it delayed raising rates because it believed inflation would be transitory and started raising rates once its view on inflation changed. What our paper shows, however, is that market participants may not have fully understood the Fed's approach: even following the many, large inflation surprises of 2021, market participants anticipated little response to future inflation. Our evidence suggests that in early-mid 2024 markets believed the Fed would be quite responsive to inflation. In particular, they believed that as inflation receded the Fed would start cutting rates. So far, that belief has been borne out.

Why do you think public perceptions of the Fed's commitment to fighting inflation shifted so late, even after inflation warnings in 2021? What does this suggest for improving communication of policy changes?

The Fed's problem throughout 2020 and 2021 was extremely difficult. Covid was unprecedented, and the ensuing inflation was the most severe in four decades. This meant that market participants did not have good historical precedents to rely on and were uncertain about how the Fed would respond. Our main message is that against a backdrop of such heightened uncertainty, words are not always enough. Raising interest rates may be necessary to help convey a commitment to fighting inflation in a timely manner.

Your paper discusses 'learning from actions'—where the public updates its views based on actual policy moves. How can central banks use this concept to better shape public expectations about inflation?

Central banks already think carefully about how the public will interpret their policy moves. What our paper provides are methodologies to help central banks to better measure public perceptions about how policy will evolve in the future. At times when public perceptions do not align with the central bank's own views, then some combination of policy moves and sharper communication may be warranted. Our paper only studies one episode, but in that episode actual policy moves were important for underscoring the Fed's commitment to fighting inflation.

How does the recent shift in perceptions compare with previous high-inflation periods, such as the 1980s, and what lessons could apply to future economic shocks?

We are fortunate that high-inflation periods are rare in advanced economies. However, since our data only start in the mid-1980s, this means that we cannot examine previous high-inflation periods. Going forward, we are hopeful that the tools developed in our paper will help central banks better monitor public perceptions so that they can take actions when those perceptions are misaligned with their intentions.